“Has anyone at the CCRC got the time, please?” – Justice Gap

From The Justice Gap we reproduce this interesting article, with its remarakable revelation that the Criminal Cases Review Commission (“CCRC”), the body tasked to investigate alleged miscarriages of justice in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, does not record the time it spends on cases:

I was astonished to learn earlier this week that the CCRC keeps no records at all on how much time that it spends working on cases.

Such record keeping and time management is a basic requirement that normally lies at the heart of law firms, which the CCRC effectively is, which rely on the billable hours system to know what work is done, by whom, and how long it took, so that they are then able to calculate how it should be costed.

Knowing how long it takes to review alleged miscarriages of justice that are submitted to the CCRC, which is well documented to be cash-strapped with a diminishing budget (see here), would also be invaluable in calls for further public funding, which is something that its defenders and critics, alike, agree is much needed.

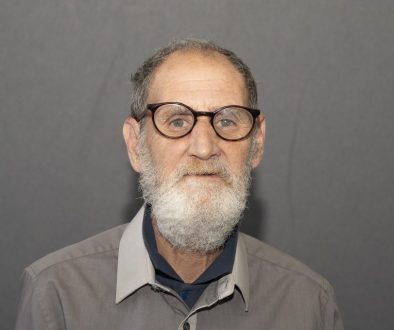

The information was revealed in a series of tweets by Mick Geen, father of Ben Geen, a former nurse who was convicted of murdering two patients and causing grievous bodily harm to 15 others while working at Horton General Hospital in Banbury, Oxfordshire, in 2003 and 2004. See below.

Ben Geen, who has so far served going on half of his 30 year prison sentence, has always maintained his innocence, and there is mounting evidence that not only casts doubt on the evidence that led to his conviction but which also questions whether any crimes were committed at all (here).

The revelation that the CCRC have no idea how much time that they spend investigating alleged miscarriages of justice was obtained in the response from the CCRC to a Freedom of Information (FOI) request from Mick Geen in late 2016 that he disclosed on Twitter on 22 January 2020.

Specifically, Ben Geen’s application to the CCRC had been rejected and Mick wanted to know:

‘After a flawed investigation & supposedly years of work I wanted to know how much time had been spent by the CCRC investigating Ben’s complex & detailed application-We were genuinely surprised at the response w (sic) received-I wonder if things are different now?’

The foregoing reply by the CCRC provides further insight into the general lack of transparency and accountability of the organisation (here).

‘We do not consider it necessary to record activity on each case hour-by-hour, day-by-day, or in a way that allows to say specifically when a case is being, as you say, worked on. We simply say that a case is under review from allocation to case closure. Case Review Managers are trusted to manage their portfolio of cases. Their managers manage their performance and keep track of how many cases they have and how those cases are progressing. Significant events in the life of a review are recorded in our case management system but this is not designed to account for the exact amount of time spent on a case or to show which days there was specific activity on this or that case. The Commission takes the view that there is no need for that sort of calculation in order for us to effectively manage our casework.’

The CCRC’s response also means that applicants are unable to evaluate the thoroughness, or otherwise, of reviews into lines of inquiry that they request in their applications.

But, despite this, applicants are expected to simply ‘trust’ that CCRC case review managers are managing their cases ‘effectively’.

Well, trust is something that must be earned and with 99% of applications currently being rejected by the CCRC (here) it is not something that alleged miscarriage of justice victims and the organisations and groups that support them feel inclined to do.

Moreover, what does it actually mean to say that the CCRC ‘takes the view that there is no need for that sort of calculation in order for us to effectively manage our casework.’

Does it mean from a managerial perspective that it has devised methods to quickly find fault with applications so that they can be rejected, and key performance indicators for processing its applications met?

Or, alternatively, does it mean from a justice perspective that it uses its special powers to undertake full investigations in the public interest into any and all lines of inquiry into claims of factual innocence to determine whether applicants like Ben Geen, and the growing number of others like him (see here), are, indeed, innocent victim of wrongful convictions and/or imprisonment as they claim?

Answers to these questions by the CCRC are welcomed but one thing is certain, such a blasé attitude to a request from the understandably concerned father of an alleged victim of a wrongful conviction who has been languishing in prison for almost 15 years and whose entire family is torn apart by the CCRC’s lack of proactivity is not conducive to fostering trust and confidence.

It just may, however, have the effect of further enhancing notions that the CCRC is a law unto itself that obscures rather than illuminates justice, which could, hopefully, strengthen the Empowering the Innocent (see here) campaign for its reform or replacement with a body that is fit for the purpose of assisting innocent victims to overturn their wrongful convictions.

From Mick Geen:

‘I sent this freedom of information request to the CCRC in March 2016 following the miscarriage of justice watchdog’s decision that: ‘There was no basis to justify the Commission referring our Son Ben Geen’s case for fresh appeal’. I had genuine concerns that due to being underfunded and under-resourced the CCRC were unable to efficiently and effectively investigate Ben’s wrongful conviction. Following the response to my FOI request I was extremely surprised to learn that CCRC appeared to lack a structured and robust internal system to monitor staff resource for performance, efficiency and cost effectiveness in the manner that I had anticipated. Following the CCRCs rejection of Ben’s application a judicial review was granted to challenge their decision. I was pleased to later learn that the CCRC had decided to take our son’s case back on with immediate effect appointing a new case review manager and commissioner. We are confident of a more positive result at the second time of asking.’

The original article can be found HERE.

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)