Why Barry George is still haunted by his conviction

We are grateful to Michelle Diskin Bates, sister of Barry George, for her kind references to Paddy Hill, Gerry Conlon an MOJO in a recent article in the Belfast Telegraph. The article concerns Michelle’s recently published book, “Stand Against Injustice” , but is wide-ranging and well worth a read:

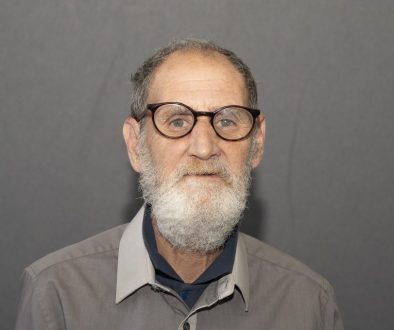

A sister of Barry George, the man who was wrongly convicted of the murder of BBC TV presenter Jill Dando nearly 20 years ago, has revealed that she received ‘invaluable’ support for her fight for justice for him from Paddy Hill of the Birmingham Six and Gerry Conlon of the Guildford Four.

And Michelle Diskin Bates says that she and her brother attended the west Belfast funeral of their ‘dear friend’ Gerry Conlon, but their presence went unreported by local media at the time in June 2014.

In a new book, Stand Against Injustice, Michelle says her brother is now living in the Republic after he was “hounded” out of England by tabloid newspapers.

In a high profile trial George was found guilty of killing Ms Dando, who was shot dead on the doorstep of her home in the fashionable Chelsea district of London in April 1999.

Michelle says her brother, who lived in nearby Fulham, had been in the Chelsea area on the day of the murder, making a series of complaints to a disability centre who after the killing reported him to police but they didn’t arrest him for another 12 months.

He was jailed for life the following year but the conviction was ruled unsafe by the Court of Appeal who ordered a re-trial and he was acquitted in 2008 after fresh doubts were cast on the reliability of gunshot residue evidence.

Despite the acquittal, George’s claim for compensation for wrongful arrest was dismissed by judges who said that “there was a case upon where a reasonable jury, properly directed, could have convicted the claimant”.

Michelle says that the judges had in effect ruled that George “wasn’t innocent enough”.

New legislation had meant that compensation would only be paid when a court quashed a conviction because a new fact had emerged to show beyond reasonable doubt that the applicant didn’t commit the offence.

Michelle says the old presumption of innocence until proven guilty had been stood on its head to the point where people like her brother had to prove their innocence to get compensation.

And Michelle, who throughout her brother’s trial and eight years behind bars never gave up on her battle to clear his name, suddenly had a new fight on her hands which features heavily in her book.

But the publication also looks back over all of the 18 years of legal struggles on behalf of her brother who before the murder was widely seen as something of a Walter Mitty character in London.

He constantly adopted false personas to represent himself variously as a policeman, a karate champion, a stuntman and a session musician with the Electric Light Orchestra.

Among the names he used was Bulsara, the real surname of Queen singer Freddie Mercury. He also apparently claimed at a wedding in Ireland that he was an SAS soldier.

In court it was said he was a “local nutter” with a personality disorder but his family said he was a “naive eccentric”.

Michelle’s book doesn’t focus entirely on her brother’s case. She says she also wrote it to inform the public about “what the justice system is doing” and she has also highlighted a number of other cases of miscarriage of justice which concern her.

Michelle, an Englishwoman who lived in Limerick and Cork for 40 years before moving back across the water, also writes about how Paddy Hill, one of the Birmingham Six who were wrongly convicted of pub bombings in the city in 1974, has been an invaluable source of guidance and support for her along with his Miscarriages of Justice Organisation (MOJO), who also counted the late Guildford Four member Gerry Conlon among their numbers.

She says that Paddy Hill approached her and offered to do whatever he could to help her and her brother.

She adds: “The organisation had all this legal stuff that I had no idea of. They gave me advice about how appeals might go. Up until then we’d had no one to turn to. No road-maps, nothing about what you should do when something like this happens.”

Michelle says Gerry Conlon had a soft spot for Barry and knew he was an innocent man. In June 2014, she received a phone call telling her that the Belfast man was terminally ill. She says that she wrote to him but she didn’t get to see him before he died.

Michelle says that she and her brother travelled to Belfast for the funeral in St Peter’s Cathedral because they felt it was important to say goodbye to him.

No reports of the funeral mention the presence of Barry George or her.

After the burial at Milltown cemetery, Michelle and her brother went to a bar to meet up with other mourners. She says that the pub had no windows and its entrance was not at the front, adding: “Once inside somebody explained that as the pub was often fired at in drive-by shootings during the Troubles, it was safer to block off the windows and to offset the entrance for security purposes.”

Michelle uses the examples in her book of the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven to illustrate the far reaching fall-out from miscarriages of justice.

“Seventeen people wrongfully convicted, 17 lives wounded beyond repair but the reality is much, much worse. For each wrongly convicted person, there is a ripple effect of damage… on the lives of parents, spouses, children, friends work colleagues, neighbours and more,” she writes.

In Gerry Conlon’s case, she writes, he didn’t just lose his liberty but his father too, adding “Giuseppe Conlon died in prison for a crime neither he nor his son committed”.

Michelle says that even though Barry George was eventually acquitted of Ms Dando’s murder, elements of the British press vilified him. “It was like open season,” she says. “And that’s why he was rescued from the country of his birth because I had to get him out of England.”

He lived in an apartment in Cork and a nephew moved in with him but his uncle eventually told him he found it too difficult to live with someone else.

In Michelle’s book, the nephew says it “makes me mad” that his uncle had to go through eight years in jail when it was “obvious he wasn’t guilty”.

He adds: “He’s been badly affected by it and I am not sure he can ever fully recover.”

Michelle agrees and describes her brother as a “released” man, not a “free” man.

She says: “Barry’s never been free since he was released from prison. The persecution of him by the newspapers thankfully stopped after he was awarded substantial damages against them. That made the bullies back off.

“But all he can think of now is being told that he hadn’t proven his innocence. At night he goes to bed with the case on his mind and when he wakes up in the morning it’s the same as he wonders how he can prove that he didn’t do anything wrong even though a court of law has already proven it.

“For Barry it never goes away.”

Michelle says her brother goes out of his apartment every day in an effort to meet people.

She adds: “He’s often described as a loner but he’s never chosen to be alone. The disability that he h as makes communication a very different thing. But he goes to the shops and chats with people and he does research on his case to see if there is anything that he has missed that he could use to get back into court with his compensation claim.”

It’s clear that Michelle has no plans to give up her campaigning for her brother or for other families affected by miscarriages of justice.

She says: “It’s a responsibility that I have – to stand in front of people and say ‘you can do it, don’t lose heart’.

“It is such a painful and lonely place to be that I just feel I have to go and talk to them and write my book so that their stories might be seen.

“My story is their story.”

Michelle says she takes comfort from the support she has received from lawyers for her call for issues surrounding cases of miscarriage of justice to be addressed.

“There are a lot of lawyers working tirelessly right now on a pro bono basis to help people who have fallen foul of the justice system. They give me great hope,” she says.

“There will always be mistakes but when there are as many as there are right now, it means that the justice system is broken and it needs to be fixed.”

Michelle is a committed Christian and she says what has happened to her brother hasn’t dented her faith.

“Not in the slightest,” she insists. “My faith was always strong and God has really been there for me and my family. When Barry was convicted we realised we were very small people battling against a huge Goliath of a legal system but God made good out of a very bad situation.”

The online Belfast Telegraph article can be read HERE.

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)