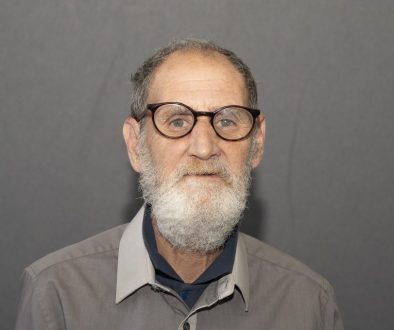

Alistair Bonnington: Malkinson offers a timely warning as Scotland sleepwalks into normalising injustice

In a hard-hitting article published today by Scottish Legal News, Alistair Bonnington identifies many of the serious concerns that we – and many others with experience of the Scottish criminal justice system – have voiced over the Scottish Government’s proposed Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill, currently working its way through the Scottish Parliament.

Those who are familiar with the author’s substantial output will know that he is not renowned as an admirer of the current Scottish government. At MOJO we are politically neutral; we are concerned only with the administration of criminal justice. From that neutral position, we identify with, and we share, the concerns expressed in the article, which we reproduce below:

The understandable furore over the wrongful conviction of Andrew Malkinson on a charge of rape in the English High Court has led to calls from many eminent lawyers for a public inquiry. The failures of the police, the Crown Prosecution Service and the Criminal Cases Review Commission add up to a disastrous miscarriage of justice. As a former prosecutor said on Radio 4: “There is nothing worse the state can do than convict and lock up an innocent person.”

Can we in Scotland be smug and say “it couldn’t happen here”? Not at all. Of course, it could and it has. The work of the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission has shown that Scottish courts have convicted innocent people, and sadly far too often.

Sometimes the commission has been dealing with cases where advances in scientific techniques of investigation have been put to use to demonstrate that the convicted person couldn’t possibly have been the perpetrator. But in Scotland, as in the English Malkinson case, reviews and further appeals have also unearthed dishonest or unreliable witnesses, failures by the police or Crown to be wholly candid with the defence, and similar shortcomings.

To guard against injustice constant vigilance is required for all criminal cases, perhaps especially emotive types such as rape. After all, the way we try persons accused of crime, particularly serious crime, is a barometer of the state of civilisation of our society.

Today, however, Scots law faces one of the most dangerous attacks on the integrity of our system of trying those accused of the crime of rape and other serious sexual crimes. That attack comes from the Scottish government in legislation they have put before the Scottish Parliament, the Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill. Since all SNP MSPs must sign an undertaking that they will support the SNP leadership irrespective of any personal views they may hold and irrespective of the interests of the Scottish public, we can hardly be confident that this attack will fail.

The bill proposes that rape trials and other cases involving serious charges of a sexual nature will no longer be tried by a jury of 15 people, but by a judge alone – and a specially-trained judge at that. The judge’s training will be in “trauma-informed practice”. Indeed, the whole thrust of the bill is based on this concept.

This may or may not be New Age nonsense which will fade in a few years to be replaced by some new miraculous discovery of another and better truth from whatever part of academia churns out such stuff. But what we can see about it right away is that it is founded on the belief that all complainers in sexual cases are “victims” who have been traumatised by their experiences. The notes to the bill actually indicate that this trauma will explain any inconsistencies or strange behaviour by the complainer.

In other words, it certainly won’t be the case that these things could arise because the complainer is lying. He or she is beyond reproach. So why bother having a trial at all? Shouldn’t we just go onto the Russian system in which the case starts with the judge asking the accused: “Why did you commit this crime?”

The various documents published by the Scottish government along with the bill seek to justify the terms of the proposed reforms. In truth the underlying philosophy which emerges from a reading of these is clearly that the basis of our criminal law should be vengeance. This is to replace our centuries-old principle of public (not private) prosecution in the public interest.

Of course, the victim of a crime has a particular and vital interest in all this. Nobody is denying that. But if we let that interest dominate and determine substantive and procedural laws then we are surely back at the “an eye for eye, and a tooth for a tooth” approach of the Old Testament. Entirely understandable and strong emotions are expressed by victims of crime. But that’s not a justification for constructing our criminal law to be the equivalent of an Albanian blood feud.

Inevitably the crime of rape is a matter which raises fierce debate. Its very nature makes it an exceptionally difficult crime to deal with in every way. In the court context it often depends on the word of one person against another.

Rape cases very seldom involve a physically violent attack on a woman. They are more commonly disputes about the presence or absence of consent. So, it’s hardly any wonder that juries find it difficult to be satisfied that the Crown has proved its case “beyond reasonable doubt” as the law requires. Accordingly, the conviction rates for rape cases are lower than the average for other kinds of crime, as I understand is the case in almost all democratic jurisdictions.

The problem in these “lack of consent” court cases is that the facts often don’t make it easy to decide if consent is present or absent. Because the Scottish jury does their job responsibly, without the cavalier “jumping-to-conclusions-based-on-prejudice” attitude of journalists and so-called experts, they find their task extremely difficult in many cases.

Ever since the SNP became the Scottish government they have been determined to increase the number of convictions in rape cases. Quite why might be a reasonable question to pose. It seems to me that the only explanation for their approach is that they believe the acquittals brought in by juries are mostly wrong. There is no empirical evidence to support that viewpoint. It is a guess – no more.

The simplistic view that nobody would ever claim to be raped unless that were true is an assertion which would never be made by those of us who have been involved in many cases in the Scots courts. But as far as I can see, that groundless assumption is the underlying basis for the Scottish government’s approach to these type of prosecutions. Looking at their overall approach, I think it’s reasonable to conclude that essentially they think that all accused are guilty – perhaps of all crimes, not just rape.

Following the introduction of this bill into the Scottish Parliament at the end of April, Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain endorsed the abolition of juries in rape cases. Her justification was largely the backlog of serious High Court trials due to the Covid slowdown of criminal business.

To reform the basis of our criminal procedure law on the basis of a temporary backlog seems an extraordinary idea. Are the annual figures for completed court cases more important than giving accused persons a fair trial which would withstand scrutiny in the European Court of Human Rights? Is this a proportionate response to a temporary problem? No lord advocate of my time in practice would ever have put forward this kind of argument. You can’t help wondering if the repeated concern of many lawyers that the Crown are now too close to the Scottish government might be justified.

Constitutionally, the most objectionable part of the bill is found in those sections which deal with the creation of a victims’ commissioner. This part reads like law from an authoritarian Soviet-style regime. In effect this commissioner is given the task of overseeing the conduct of the judge-alone rape trial court. There is little doubt that he or she will be able to take action if any “un-Soviet” decisions are made by “off-message” judges.

This individual will in effect assess – on the suitably absurd basis of “trauma-informed practice” – how everyone involved in the criminal justice system is performing.

Isn’t the job of supervising the standards followed in our courts one for the lord justice general? It was when I practised law. I have never heard anyone complain that the LJG had failed to carry out that function properly. So why adopt the methodology used by dictatorships?

It is extremely suspicious that the individual holding this victims’ post is to be given absolute privilege protection from defamation actions. This the strongest form of protection from a defamation action. It is afforded in our law only in the most extreme circumstances – such as speeches in Parliament.

It looks as if this individual is expected to say the most dreadful things about judges, and perhaps others working in the justice system. These could well be completely unjustified and inaccurate things, which must be why the Scottish government is worried about defamation. The commissar can bask in the protection of absolute privilege no matter how outrageous the statements. Again, one can’t help wondering if such rants will be encouraged by the Scottish government for political ends? Surely not. But what on earth is this weird provision doing in this bill?

The independence of the judiciary is a fundamental and essential part of any democracy. The separation of the three arms of government – legislature, executive and judiciary – is recognised worldwide as the basis for a civilised and democratic society. The Scottish government in this Victims Bill propose to discard that system and instead have executive supervision of the courts through this commissioner. Of course, we are told in the bill that this post will be independent of the Scottish government. No political party has ever been as opposed to independence of thought or deed as the authoritarian SNP.

Doubtless they would have us believe that it is only for the extreme cases such as rape where they wish to impose this offensive interference. The lessons of history are clear. If they get away with this they will be encouraged to do the same again.

I used to say, in my practising days, that if I supported the death penalty I would support its use in rape cases before murder. That was because I regarded rape as such an appalling crime. But my revulsion for the crime itself and its perpetrators has never led me to the position in which I promote an unsafe method of trial in order to convict accused persons who might be rapists, but equally might be innocent. “Might be guilty” can never be good enough.

To examine any contested court matter from the perspective of “goodies and baddies”, as the Scottish government do in their bill is as stupid and infantile as it sounds. As we all know, the real world has never been as simple as that. It’s a fiction from storybooks and soppy movies. But this is exactly the kind of thing which suits our simplistic Scottish politicians: “Let’s ignore the facts, they’re far too difficult.”

I can’t help noting the lack of protest from the Scottish public to what is in effect an attack on the independence of the Scottish democratic system of government – albeit that our history shows that democracy was an import into Scotland from elsewhere. The separation of powers is fundamental to a democratic system. The Victims Bill seeks to have the executive take over the function of the judiciary by supervision.

In Israel and Poland similar moves by authoritarian governments brought thousands of demonstrators onto the streets. Many Israeli intellectuals have been interviewed on TV saying that they will leave the country if the government there succeeds in compromising the independence of the judiciary.

Do Scots just not care? Do they not fully understand the enormity of what is proposed? Have they given up, realising that the SNP don’t care about injustice but prefer to pander to the prejudices of single interest groups in the hope that it will garner them votes?

When I used to teach law graduates criminal procedure law, I told them that we had our own independent system in Scotland which was much superior to the English equivalent. I assured them that in Scotland accused persons received a fair trial and this was something which we as Scots lawyers should be proud of.

Even today, before the Victims Bill, the interference by the SNP government in our procedural law has jeopardised fair trials. Should it become law, I would have to tell my class that a fair trial is not something we do in Scotland.

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)