Ex-prisoner’s cry for help over indefinite jail term before his death

The Independent has today published an article which, whilst dealing with English law, highlights a major weakness in how we do justice in Scotland also.

The article, which we publish below, draws attention to the appalling consequences of a failed experiment introduced by section 225 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (with effect from 2005) by the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett. The “IPP” sentence was designed to allow the indefinite incarceration of offenders whose offending was not sufficiently serious to warrant a life sentence. It was, in reality, a life sentence by another name. As with a life sentence, the offender was handed a “tariff” – a finite period that had to be served before eligibility for parole. As with a life sentence, parole was subject to licence conditions that subsisted for the remainder of the offender’s life. The IPP sentence was abolished in 2012. Those on whom it was imposed, however, remain subject to its draconian conditions.

As you read the article, please consider this. We have, in Scotland, an equivalent “indeterminate” sentence. Here, it’s called an “OLR” – Order for Lifelong Restriction. It is identical, in its effect and consequences, to the discredited and abandoned IPP. The OLR however has not been abolished. It remains available to judges in our High Court of Justiciary.

The true nature of this sanction may best be illustrated by an example from real life. Some time ago we were approached by a prisoner who had been made subject to an OLR. He had been convicted of a Breach of the Peace. He did, certainly, have a history of similar offending, but he was sentenced in respect of Breach of the Peace. The tariff imposed on him was 6 months. When he contacted us he had already served 9 years.

“I’m stuck in a never-ending cycle of which suicide is quite possibly really the only way out.”

These were the devastating words of a man struggling under an indeterminate sentence as he issued a cry for help to justice secretary Alex Chalk.

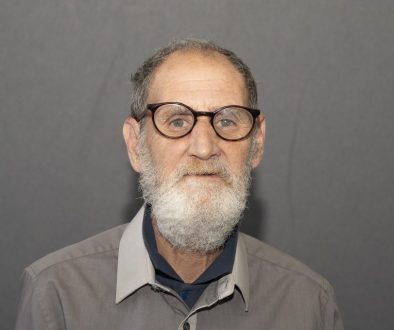

Matthew Price, 48, was handed an imprisonment for public protection (IPP) sentence in 2010 for seriously wounding his friend, with a three-year minimum tariff.

The “hopeless” sentences, in which offenders were handed a minimum tariff but no maximum, were abolished two years later amid human rights concerns after scores of prisoners were left languishing in jail with no hope of release.

However they weren’t changed restrospectively, leaving thousands struggling under sentences branded the “single greatest stain on our justice system”.

Unlike hundreds of IPP inmates who have served more than ten years longer than their minimum tariff, Mr Price was released in 2013. However he was subject to strict decade-long licence conditions which can see IPP offenders quickly recalled to prison for even the most minor breaches.

When he penned an email on 22 May to Mr Chalk and other politicians, including then justice minister Damien Hinds, Mr Price, from Leeds, had spent almost ten years in the community without reoffending.

But amid ongoing mental health struggles following the death of his father, he still lived in perpetual fear of being returned to prison. And he was terrified that seeking mental health support or taking medication would be interpreted as an increase in his risk by probation officers – damaging his chances of ever being freed from the draconian licence conditions.

His fears were exacerbated after a previous attempt on his life in 2020 had resulted in increased supervision by probation officers.

Speaking of his anguish, he wrote: “The truth is I need mental health support and I feel I need to be back on medication to be able to cope with this sentence but I’m too scared to ask for it because doing so will go against my chances of ever bringing my sentence to an end.

“My mother can’t believe that she lives in a country where this is actually happening in this day and age. I don’t think the wider public can either.

“I’m stuck in a never ending cycle of which suicide is quite possibly really the only way out.

“Asking for help will go against me, not asking for help will most likely kill me.”

He insisted he had taken responsibility for his crimes but could see no escape from the sentence, adding: “I’ve never denied my offending and taken full responsibility.

“Of course I needed to go to prison as a result of my actions but how can it be right that I’m being expected to cope on a irredeemably flawed sentence, that’s inhumane and was abolished in 2012 and also be on a potentially lifelong licence that might never end, and feel fearful to ask for mental health support help.”

In the open letter, shared following his death by his legal team and highlighted in podcast Trapped: The IPP Prisoner Scandal, Mr Price blasted IPP sentences as the “death penalty by the back door”.

It comes after The Independent revealed seven IPP inmates had taken their own life in prison since February, bringing the total death toll to over 80 lives lost to suicide while serving IPP jail terms.

“The fact is the never-ending and never knowing nature of this sentence feeds poor mental health. Even if they’d hung me there would have been a definite ending and clarity,” he wrote.

“The truth is that this long abolished IPP sentence has proved to be capital punishment through the back door in many cases with those who have seen taking their own lives as the only way out growing rapidly recently.

“This is a cry for help because this never-ending sentence and the not knowing has crushed and broken me and I don’t know what to do for the best anymore.”

Mr Price’s lawyer Emma McClure was helping him apply for his licence to be terminated in the weeks before he died. She was the last to speak to him before he took his own life on 16 June.

She told The Independent: “Almost every call with him had some element of he felt stuck, he felt he was never going to escape from the situation.”

Although probation reviews do not prohibit offenders from accessing mental health support, in practise mental distress can be interpreted as an inability to cope and a potential risk, she said.

Her colleague Andrew Sperling said his death is even more tragic given under new proposals to reduce the IPP licence period to three years announced by Mr Chalk this month, Mr Price would have finally been free.

Although the changes are welcome and “long overdue”, they came too late for Mr Price, he said. And they do not help almost 3,000 unreleased IPP inmates – including recent cases highlighted by The Independent such as Wayne Bell, who was jailed for a minimum of two years for taking a bike but has served more than 16, and Thomas White who has served 11 years for stealing mobile phone.

“The problem is there are still a whole load of people who are still in custody and have never got out,” Mr Sperling added.

Mr Chalk has so far refused cross-party Justice Committee recommendations to resentence all IPP prisoners.

A Ministry of Justice spokesman said: “Our thoughts remain with the friends and family of Matthew Price.

“We are curtailing licence periods to give rehabilitated IPP offenders the opportunity to move on with their lives and have put in place additional community mental health support for those at risk of self-harm or suicide.”

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)