DNA Profiling – the role of Artificial Intelligence

Over coming weeks we will be publishing a series of articles by our volunteer staff, offering their personal insights into the work that they, and we, do here at MOJO, and into the wider issues that we face daily. Our volunteers are the lifeblood of this organisation. We hope that you will find their observations informative, and interesting.

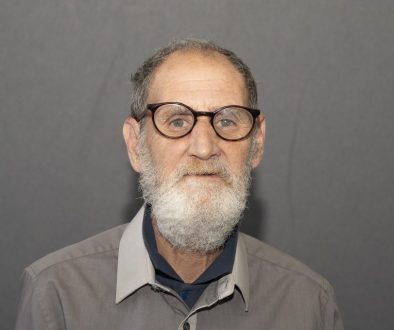

The following article, by our volunteer caseworker Calum Harris, looks in detail at recent developments in the approach to DNA evidence, its analysis and use in the criminal justice process.

A recent article by Karen Richmond, a doctoral candidate at the University of Strathclyde whose research focuses on forensic DNA profiling, and the use of algorithms within the criminal justice system, prophesied the potentially revolutionary impact that artificial intelligence (AI) could have on DNA evidence. We at the Miscarriages of Justice Organisation wish to offer an alternative legal viewpoint on its future in the criminal justice system by likening AI to the science of probabilistic genotyping in DNA evidence, whose rapid enrolment in criminal trials worldwide has posed a grave risk to of false conviction to many criminal accused. Only recently has the tide begun to turn and various judiciaries have started to accept its shortcomings. Ultimately, if the admissibility procedures are properly applied by the courts, we hope that AI is a long way from entering the criminal trial.

Richmond rightly questions “how can we trust technology to provide vital evidence if we can’t interrogate how it produced that evidence in the first place?”[1] Generally speaking, AI refers to machinery that is programmed to act like humans or to display other human traits, such as problem solving and learning. Techniques as proposed, in theory, could reduce miscarriages of justice as they hypothesise to eliminate confusion currently caused by the phenomenon of ‘transfer and persistence’. This is the phenomenon that DNA from one individual can be transferred through direct contact with other individuals or even the handling of inanimate objects, resulting in said individual’s DNA showing up in places they have never physically been. How this AI software can be programmed to accommodate such a phenomenon – when human knowledge of the exact extent and tendencies of DNA transfer, nor the varied levels of persistence with which each individual’s DNA sheds and lingers on surfaces it touches, is not yet sufficiently developed – is hard to justify or explain.

Legally, the main problem that the lack of knowledge of the AI mechanics poses is how such evidence will ever make its way into the criminal trial. Probabilistic genotyping software, specifically the STRmix programme, has recently come under fire in the United States. This software is programmed to produce a likelihood ratio which compares the probability of a piece of DNA evidence if one hypothesis is true against the probability of same piece of evidence if another specified hypothesis is true. What it does not measure is the probability of either proposition having actually occurred. This is the equivalent to confusing the probability that a dog is a four-legged animal with the probability that a four-legged animal is a dog,[2] the prejudice such a mistake places on the accused can be easily inferred. What it certainly does not measure is key question of the likelihood that an accused is guilty. The case of United States v Gissantaner[3] concluded with regards to the complex DNA evidence in that case presented through a likelihood ratio developed by probabilistic genotyping that:

“it is a combination of forensic DNA techniques, mathematical theory, statistical methods (including Monte CarloMarkov Chain modelling, as in the Mote Carlo Gambling venue), decisional theory, computer algorithms, interpretation, and subjective opinions that cannot in the circumstances of this case be said to be a reliable sum of its parts. Our system requires more.”

It must be noted that this decision was arrived at on the back of a year long Daubert admissibility hearing process which contested the opinions of two world leading experts in the field who acted neither for the defence nor the prosecution. The court arrived at the decision not to admit the evidence by considering (among others) the following questions:

- Whether the theory or technique can and has been tested?

- Whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication?

- The known or potential rate of error of the particular scientific technique or theory and the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique’s operation?

- Whether the theory or technique has general acceptance in the relevant scientific community?

The court concluded that the STRmix had not yet been tested adequately. However, the technique can be tested, and defences and prosecutors alike have been allowed access to the codes used. The refusal of the software manufacturers to release its innerworkings of AI leave it impossible for the technique to ever be tested. Therefore, AI would fail at this stage as it cannot be tested. Nor has it been tested adequately.

The question of peer review was rather inconclusive in Gissasanter for much of the peer review had been conducted by and/or signed off by the software’s inventors and developers, funded by the commercial enterprises who own the software. Not enough is known about AI to answer this. The bar was set rather low by the court, who recognised one or two independent reviews as probably sufficient in this light. Commercially backed peer review will likely emerge in a similar way from AI manufacturers but is not the main concern of this article at the current stage.

The two experts wildly disagreed on the error rate and the levels of operating standards of genotyping software. The court took this disagreement to amount to a substantial inadequacy of reliability. As Richmond points out, “AI-based software has an even greater transparency problem than probabilistic genotyping software did, and one that’s currently fundamental to the way it works. The exact way the software works isn’t just a commercial secret – it’s unclear even to the software developers.” Consider this alongside the view of the Court in Gissasanter that “the concluding lesson from the extensive testimony and complex documentary evidence presented in this case is that the specific care required for low-template, low level DNA testing has largely faded into the background as the shortcomings of the technology and need for stringent controls on its use have been glossed over in the rush to embrace the technological advancements.” The resulting situation is that the sufficient level of care necessary to operate such sensitive techniques can never be achieved nor can they be controlled, for you cannot control something in the prescriptive manner required by a court of law if even the manufacturers of the product do not understand exactly how it functions, and thus what measures must be in place to control it.

Lastly, Gissasanter did not view there to be sufficient acceptance in the scientific community (what constitutes such a community was a point which was debated also and will inevitably re-arise in any future attempts to legalise AI technology). Bess Stiffelman summarises the state of affairs well writing in an informative article (which we encourage all lay readers with an interest in DNA evidence to read) that “in short, the technology and science is so disputed, that there is insufficient consensus in the scientific community regarding the admissibility of these LRs.”[4] A similar problem as detailed above once again arises. If nobody entirely knows how AI works and it is reliant on constantly evolving algorithms, general scientific acceptance is theoretically impossible as neither the foundational basis for the technique nor the results it produces can be known, let alone scrutinised and debated to the extent of general scientific acceptance. Furthermore, the Daubert standard appears to be interpreting disagreement between two experts as amounting to the disputed technique falling short of general scientific acceptance, meaning foreseeing AI’s admissibility to criminal proceedings – certainly in the United States – is highly problematic.

It must be acknowledged that Scotland does not currently possess such stringent or sophisticated tests as the United States. Forensic scientist Allan Jamieson asks, with regards to Gissasanter, “this was 18 months of consideration and court-appointed experts subjected to strong judicial interest and scrutiny. Has a similar investigation occurred in the UK?”[5] In Scotland, Young v HMA[6] offers the senior judgement on the admissibility of expert evidence (which AI would of course be presented as). Kennedy v Cordia,[7] a civil case decided in the Supreme Court, appears to be being used in conjuncture in Scottish criminal proceedings but has not yet been adequately adjusted to these proceedings. Young v HMA does require that expert evidence must “proceed on theories which have been tested (both by academic review and in practice),” which as already explained above, cannot surely be adequately done without understanding of its exact mechanical foundations or functions.

More importantly, Young also requires evidence

to “follow a developed methodology which is explicable and open to possible

challenge.” As Richmond rightly points out, “It is a fundamental tenet of the

law that evidence must be open to scrutiny. The jury

cannot rely on bald assertions (claims made without evidence), no matter who

makes them and what expertise they have.” Evidence cannot be challenged if its

provenance is not only unclear but unknown. While probabilistic genotyping

poses problems of presenting a figure, which tries to disguise itself as the

accused’s guilt, AI is asking the Judge, jury and legal representatives to

accept evidence with an unknown scientific validity. This cannot, but

encouragingly, in the view of this writer, will not be accepted.

[1] Karen Richmond ‘AI could revolutionise DNA evidence – but right now we can’t trust the machines’ (2020) The Conversation.

[2] Allan Jamieson ‘Hidden in plain sight; the problems with current DNA evidence’ (the barrister, 8 January 2019) <http://www.barristermagazine.com/hidden-in-plain-sight-the-problems-with-current-dna-evidence/>

[3] United States v Daniel Gissantaner, Western District of Michigan, Southern Division, Case 1:17-cr-130 (2019).

[4] Bess Siffelman ‘No Longer the Gold Standard: Probabilistic Genotyping is Changing the Nature of DNA Evidence in Criminal Trials’ (2019) Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law 24(1).

[5] n. 2.

[6] Young v HMA 2014 SLT 1037 21.

[7] Kennedy v Cordia (Services) LLP, 2016 S.C. (U.K.S.C), 59.