On This Day 2009

Today, we repost the following article from the Guardian surrounding eye-witness mis-identification and the wrongful conviction of Billy Mills.

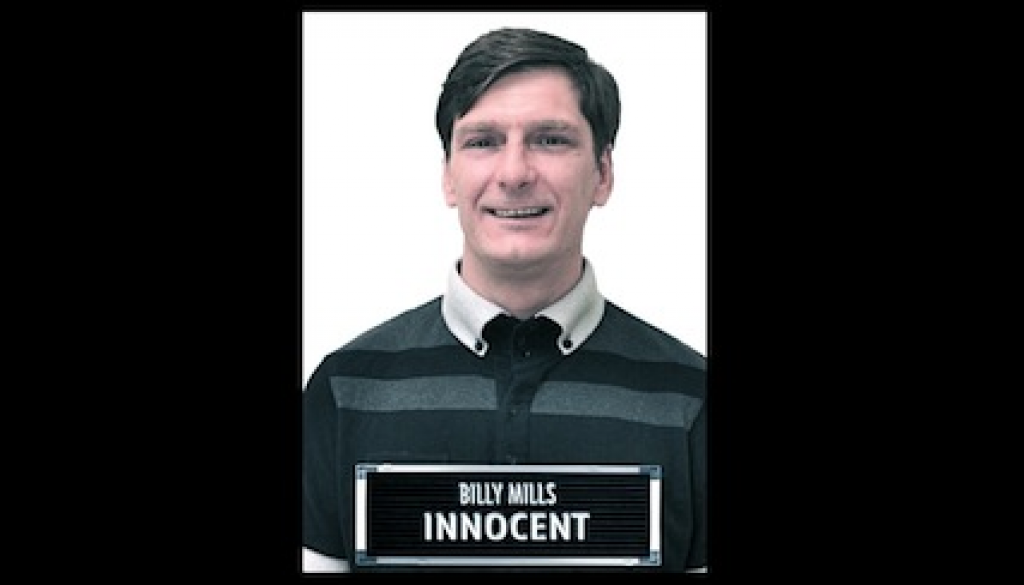

Billy was found guilty of the robbery of a Royal Bank of Scotland branch in Partick, Glasgow, in May 2007, and sentenced to 9 years in prison.

The prosecution relied on the evidence of police officers who had viewed CCTV stills and the evidence of eyewitnesses who spoke to the robber having a strong accent which sounded, to them, South African.

In April 2009, at the Court of Appeal in Edinburgh, Mr Mills’s conviction was overturned. The Lord Justice Clerk, Lord Gill, said: “The new evidence confirms all of our reservations about this conviction. We agree that there is clearly reasonable doubt. We conclude that there has been a miscarriage of justice and allow the appeal.” The original article can be found HERE.

Wrongful conviction throws spotlight on unreliability of eyewitness evidence

William Mills was sentenced to nine years for bank robbery based on police identification from CCTV images, despite their showing a man in sunglasses with a scarf over his mouth and chin

Four people said they recognised William Mills as the man who robbed a bank in Glasgow’s West End – but all of them were wrong. Having endured a dawn raid on his family home and roughly a year in prison, Mills was freed earlier this year.

With more eyewitness evidence being gathered than ever before, could he be part of a growing trend of wrongful convictions?

“It was about 5.30 in the morning when I heard my partner Toni shouting loudly: ‘They’ve got guns, they’ve got guns’,” said Mills. “I jumped out of bed and ran to look through the spy hole but all I could see outside was a mass of black, people in black.

“My two young girls and my partner were standing in the hall so I told them to stay back and I opened the door. The whole communal landing was covered in police, all dressed in black with ski masks on, with big rifles and shields … They were telling us all to get on the floor and there were red dots from the guns everywhere.”

Mills described how he was handcuffed, wearing only his boxer shorts, as the armed police stood by. The whole of his street had been cordoned off. “I had no idea what they wanted. I kept on trying to ask: ‘Why are you doing this?’ It was only when they got me to the police station that they told me they wanted me for a bank robbery.”

Mills, from Partick, Glasgow, was arrested in May 2007 and held on remand for stealing £8,216 from the Royal Bank of Scotland’s Dumbarton Road branch. Two policemen had identified Mills from CCTV stills and two witnesses – customers in the bank at the time of the robbery – picked him out at an identity parade. A year later he was found guilty and sentenced to nine years in prison.

Mills was freed earlier this year, six months into his sentence. DNA evidence found on a door stopper linked a convicted bank robber, Michael Absalom, to the crime. Including the time he served on remand, he had spent roughly a year locked up for something he did not do.

“I’m still suffering through what they’ve done,” he said. “My family’s suffering. I’m going to see a psychologist because I don’t like going out now … It was crazy, man, just unbelievable; you just never think it would happen to you. On remand I was locked up 23 hours a day, that was for six months.

“Being away from my family was the hardest thing, and not being able to protect my children [when the police came]. I felt so helpless. After they found me guilty, I’ll never have faith in the judicial system again.”

So how did it happen? “This was a prosecution that stood or fell by eyewitness identification alone,” said Lord Gill, the lord justice-clerk at Mills’s appeal. “That is a form of proof that has been shown to be, in some cases, a dangerous basis for a prosecution.”

It was certainly not the first time that eyewitnesses had got it wrong. As early as the 1970s there was sufficient concern in England that eyewitnesses were making enough mistakes to warrant an investigation into several miscarriages of justice. This investigation resulted in the 1976 Devlin report, which recommended that no one should be convicted on the basis of eyewitness evidence alone. But this recommendation was never made law, and technological advances have meant that identification evidence is now more easily available than ever before.

Many police forces in England and Scotland use video line-ups instead of live identity parades. This has made it cheaper and easier to run a line-up, and means that many more are being conducted. “There are currently up to 100,000 line-ups held per year, compared to around 2,000 at the time of the Devlin report,” said Professor Tim Valentine, a leading eyewitness researcher at the University of London. “Errors are going to be proportionate to the number of procedures that are run, so I wouldn’t be surprised if there are more errors now than there used to be.”

The proliferation of CCTV cameras has also led to an increase in the availability of identification evidence. According to the Police Foundation, the UK now has more surveillance cameras than any other country in the world, and footage is used to solve around 160,000 criminal cases a year. When CCTV footage is used to identify someone in court, a police officer or relative may claim to recognise that person from the footage, a jury might be asked to compare the defendant to someone in CCTV images, or an expert can use facial mapping techniques to compare the defendant’s face to that of the suspect.

Under the Turnbull guidelines – introduced in 1977 by a judge who found that visual identification “can bring about miscarriages of justice and has done so” – a judge has to warn the jury of the need for special caution when relying on such evidence. But eyewitness testimonies can still be one of the most persuasive types of evidence a jury will hear. “A witness standing up and saying: ‘That’s the man, I saw him, I will never forget his face’ is extremely compelling to a jury,” said Valentine. “Witnesses can be completely honest and be mistaken.”

Psychological experiments have shown that facial recognition from CCTV can be as prone to error as traditional eyewitness evidence. In an experiment which looked at 600 identity parades, a fifth of eyewitnesses picked the wrong person, Valentine said.

In a recent experiment conducted by Valentine and Dr Josh Davis, 33% of participants identified the wrong person from close-up, high quality, video footage of the suspect’s face. CCTV images are often bad quality, and the angle and lighting can change someone’s appearance.

“You’d probably recognise your mother from a CCTV image, but recognising somebody you don’t know well is very difficult,” Valentine said. On top of this, in Mills’s case the suspect’s face was obscured by dark glasses and he had a scarf over his mouth and chin for most of the robbery. Yet two policemen were allowed to testify that they recognised Mills from the CCTV image.

At Mills’s appeal Lord Justice Gill expressed his unease. “It is a matter of concern that an important part of the case for the prosecution was the evidence of two police officers, neither eyewitnesses, who made positive statements that Mills was the robber on the basis of looking at CCTV stills,” he said.

An alarming aspect of Mills’s case is that in some ways he was actually extraordinarily lucky. Having suffered the misfortune of being wrongly convicted because of faulty identification evidence, he was then very fortunate that both DNA evidence and a plausible alternative suspect were available to set the story straight. Given that DNA evidence is found at less than 1% of crime scenes, others in his situation may well not be so lucky.

“Without the DNA evidence there’s no way we would have won an appeal,” said Mills’s lawyer, Liam O’Donnell . “They would have said there are four identifications, it’s up to the jury to assess the identifications and they’ve accepted them. End of story.”

Even with the DNA evidence Mills was initially refused an appeal. It is very rare that someone is granted an appeal on the grounds that eyewitnesses in the original trial may have been mistaken. “I can think of at least three men I know of in prison now on the basis of what looks like unsafe identification evidence,” said Valentine.

“There was a time when if someone in prison told me they were innocent, I’d say: ‘Nah, I don’t believe you,” Mills said. “But now I’d have to consider it. Who’s to say there aren’t more people like me out there?”

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)