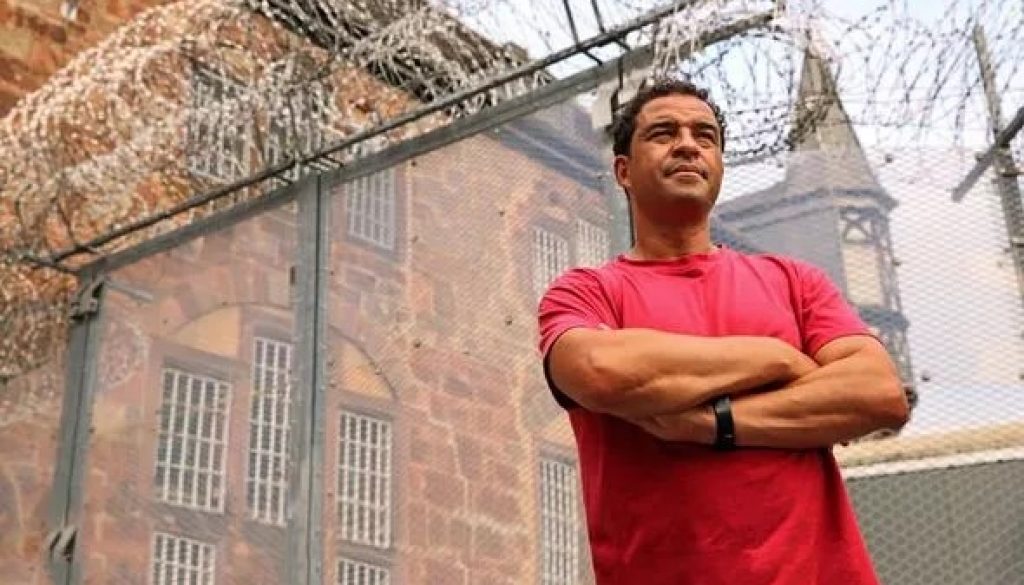

Raphael Rowe: “I wouldn’t be such a successful journalist now”

Raphael Rowe was one of three men wrongfully imprisoned, having been sentenced to life for murder and robbery at the Old Bailey in March 1990. Dubbed the ‘M25 Three’ after London’s circular stretch of motorway and the locus of the crimes, Rowe, alongside Michael Davis and Randal Johnson, have always and consistently maintained innocence.

During the early hours of the morning of 16 December 1988, three individuals embarked on a crime spree of robbery and violence, which ultimately led to the arrest of the ‘M25 Three’ and their subsequent wrongful conviction. There were flaws in the police investigation and serious inconsistencies and discrepancies in the prosecution’s case.

Rowe attributes his success as a journalist to his time spent in prison for a crime he did not commit. Best known for his investigative work with BBC’s Panorama, Raphael’s efforts to clear the name of our client Barry George following his wrongful conviction for the murder of Jill Dando is considered pivotal in Barry’s eventual appeal.

Success stories of victims of long-term wrongful imprisonment are few and far between but Raphael’s journey shows what can be achieved for our clients post release.

We repost the following article from The Express online from 29 July 2020, which reflects on his time spent in prison and his popular documentary series “Inside the World’s Toughest Prisons” available on Netflix.

The original article can be found HERE.

Raphael Rowe: ‘It’s scarred me for life’ – Netflix star on his wrongful murder conviction

RAPHAEL Rowe is a man who has witnessed the face of evil more times than he would like.

He knows what goes on inside prison walls because he lived it – 12 long years behind bars after being wrongly convicted in 1990 of murder and robbery in the notorious case dubbed the “M25 Three murders”. Now as presenter of the Netflix documentary Inside The World’s Toughest Prisons, he has visited some of the most dangerous jails on the planet interviewing serial killers, murderers, drug lords and rapists. What makes his series so different from others is that he goes in like an inmate rather than as a reporter. “From the moment I step out of that van, those guards treat me like any other prisoner, hence they strip search me,” he says.

The team involves him, two camera operators and occasionally a fixer or translator. There is no hired security and he starts each visit in handcuffs in a police van. All in all, it makes for gripping viewing.

His nerve-shredding encounters with monsters include Brazilian prisoners who decapitated their rival inmates during riots before using their heads as footballs.

Separated only by bars at a penal institution in north-west Ukraine, he spoke to a homicidal maniac, Serhiy Tkach, who suffocated young girls and women before desecrating their corpses. Jailed for the murders of 37 female victims, Tkach ultimately claimed responsibility for 100 killings in total before his death in 2018.

Now for series four, Raphael, 52, has visited Paraguay, Germany, Mauritius and Lesotho – encountering scenes so shocking his jaw physically drops on camera.

“When I walked through Tacumbú penitentiary in Paraguay, I could not believe my eyes,” the straight-talking south Londoner reveals. “I’ve seen inside many prisons and have witnessed all kinds of conditions but I had never seen anything like this.”

The prison population was four times over capacity, and guards were outnumbered 125 to one, with the worst offenders squeezed into an “overcrowded slum” where men openly smoked crack and killed one another for mattresses.

Raphael’s first impression was that it was completely lawless.

“It was terrifying to see guys sleeping outdoors in the open air, openly using drugs and carrying knives,” he says.

Inmates were encouraged by guards to run their own businesses or find other means of hustling to survive – he met Edgar who launched a “restaurant” delivering food to wealthy prisoners in their cells.

Elsewhere, Raphael spoke to one dishevelled man rummaging through the prison’s off-loaded rubbish to find cigarette butts, soap and rotting food he could cook to sell to others. “It’s about survival,” Raphael explains. “It’s about the governments and officials not having the resources to provide like other prisons do.”

Raphael’s own miscarriage of justice was quashed by the Court of Appeal in July 2000.

By that point he was 32 and had spent more than a third of his life in prison, locked up in 1988 aged 19 after being wrongfully convicted as one of the “M25 Three”, a gang who robbed Surrey residents.

“It’s scarred me for life,” he says candidly, “the psychological and physical harm of being in prison for a crime I didn’t commit.”

His freedom was eventually secured with help from the Press and, during his time inside, Raphael studied journalism.

“I wouldn’t be such a successful journalist now had I not learned the skills of being a meticulous researcher because I had to research my case in the confines of a prison cell going through every document,” he says.

Considering what he has lived through, however, it seems remarkable he would ever walk through another set of prison gates.

“It wasn’t an easy decision and one I did not take lightly,” he says. “I know what it’s like in prison, I know what the individuals are like, what’s key for police and what differences can be made in the mindsetof prisoners.”

Having taken over when original host, Irish journalist Paul Connolly, left after season one, Raphael wanted viewers to understand how prison life varies across the globe. Some institutions focus on punishment, others promote rehabilitation.

“People can draw their own conclusions about people who are in prison, why they are there and what happens to them while they’re inside,” he says.

“We’re always, rightly, told that we’re safe because the bad guy is locked up but it is what happens next that is key.”

In Maseru Central Prison in the mountain kingdom of Lesotho in southern Africa, he met a man who had murdered his four children and cut out their organs on the orders of a witch doctor. “What I still can’t get my head around is how even under the influence of some hallucinating drug you could take the life of a child, and not just one but all of them at the same time,” Raphael says. “And cut the heart out of a kid? Look, I try to remain as professional as I possibly can when I’m interviewing these people but I’m human. I have feelings and thoughts, and sometimes you can see that in my face.”

The moments where he cannot hide his disgust are when he meets rapists, who he describes as the “cruellest and wickedest” of all criminals.

In Lesotho, nearly half of all inmates were locked up for rape, while one third had HIV.

“I find it a challenge to stand and look a man in the face and ask him why he raped a child, a woman, or a man for that matter, and ask him in detail to try and understand the mentality,” says Raphael. “I can imagine the scars that have been left behind in that individual will be something they will never be able to brush off and will live with them long after the prisoner is freed.”

In Paraguay, an inmate threw a snooker ball at a crew member’s head and, in Lesotho, Raphael was told his safety could not be guaranteed. “I was told I was on my own and needed to be very careful because prisoners might rape or hurt me,” he says.

His visit to the fortress-like Melrose Prison in Mauritius reminded him of his own time behind bars. “Its structure and architecture was similar to the dispersal prisons I spent time in with lots of fences, iron doors, gates and locks,” he says. “There are moments like that when I have flashbacks.”

When imprisoned for real, Raphael was often segregated in his early days because he would “not conform to the regime”.

“I was not prepared to accept my plight, and never did in all the years I was in prison,” he says. “This made things confrontational between me and the guards because they are there to do a job and that was to make sure I did what was required of a guilty, convicted prisoner – and that wasn’t me.”

His anger sometimes put him at odds with his parents and three older sisters who visited regularly and tirelessly campaigned for his innocence on the outside. “There are many things that I regret saying to my family when I was in prison that was born out of frustration,” he admits. Nine months after his release, he secured a job on BBC Radio 4 as a reporter. “I had dreadlocks, brown skin and was a working-class boy with prison slang when I joined – and yet here I was reporting on the Today programme,” he recalls.

Later, for Panorama, he investigated the Jill Dando murder, discrediting the forensic evidence that had been used to convict Barry George, who was retried in 2008 and subsequently freed.

“Nobody has taken the unique journey I have,” Raphael continues. “That’s because I’ve embraced what happened to me rather than allow it to continue to destroy me in the way that it did when I was in prison.

“Don’t get me wrong. When I was there, I was bitter. I was twisted and volatile but I wasn’t going to allow it to control me in the same way on the outside.”

He pauses briefly, before adding: “It doesn’t mean I’m able to control the misery that’s set in having been wrongly imprisoned because every day inside was a depressing moment and so those psychological scars are with me for the rest of my life.”

If there is cause for optimism, Raphael reserves it for the maximum-security Halden Prison in Norway. Often referred to as the world’s most “humane” jail, its entire approach aims at rehabilitation.

“They provide each individual with the right therapy or skill set while in prison, so when they come out people wouldn’t mind them being a neighbour.

But it’s also about their relationship with prisoners, how they respond and interact with them.”

He believes funding is not the only answer when it comes to getting the question of prisons right.

“The key is knowledge and sharing that with prisons around the world like Norway. Then you can make a real difference.”

Series four of Inside The World’s Toughest Prisons, hosted by Raphael Rowe, is available on Netflix now

![16[2]](https://mojoscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/162-1024x768-394x330.jpg)