The Innocent Prisoner’s Dilemma

In our criminal justice system, the victims of miscarriages of justice are a class of victim often overlooked. It is not disputable that, as in any system in which human fallibility plays a part, in our justice system the wrong person can find himself in the dock and, ultimately, be convicted. In issues of credibility or reliability, the wrong person can be believed. However, by design, the system places public confidence and the perception that the system works above all else. Our clients protesting their innocence are left voiceless. Our clients fortunate enough to have overturned their convictions and to have been completely exonerated face comments such as “gotten away with it”, or “no smoke without fire”.

On 16 January 2020, our organisation ran a piece on “Suzanne’s Law” (https://mojoscotland.org/suzannes-law/) – a proposal that parole be denied to prisoners convicted of murder who fail to disclose the location of a victim’s body, without consideration of those maintaining innocence. The paradox of having to accept further repercussions based on a lack of remorse or not addressing your offending behaviour for a crime you did not commit, or where no crime has taken place at all, is a universal reality for our clients. Prisoners before the parole board maintaining their innocence are caught in an impossible, Catch-22 which US law professor Daniel Medwed calls “the innocent prisoner’s dilemma”.

Such prisoners have been labelled as ‘deniers’ with no account taken of the various reasons for maintaining innocence, nor the undeniable truth that some may actually be innocent. These prisoners once were unable to achieve parole unless they undertook offence-behaviour courses that required the admission of guilt as a prerequisite. Innocent prisoners were given the choice between freedom, in exchange for claiming guilt, or remaining imprisoned and telling the truth. This situation is not quite as stark as it once was. In England, and to a lesser degree Scotland, those maintaining innocence have access to limited training for freedom which I have been advised by clients in custody are labelled “deniers’ courses” within their prison.

It is important to note that it is not for the Parole Board, who operate within tightly framed statutory parameters, to determine guilt or innocence. They are not entitled to look beyond a conviction. That is the function of the Appeal Court and the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission. The Board’s remit extends only to the assessment of risk, and the primary concern is always the safety of the public. We will never know the Parole Board’s true feelings on any individual claim of innocence.

“Denial is not a valid measure of risk. In fact, research has shown that prisoners who openly admit to their crimes have the highest risk of re-offending.” (Gabe Tan, 2011)

UK research has demonstrated that prisoners who freely admit guilt are more likely to reoffend than those maintaining innocence. A ten-year study of 180 convicted sex offenders by Harkins, Beech and Goodwill found prisoners who claimed to be innocent were the least likely to be re-convicted, and that those who ‘admitted everything’, claiming to be guilty, were most likely to re-offend. Whereas studies elsewhere in the world conclude that there is no demonstrable link between an admission of guilt and recidivism. The Prison Reform Trust’s Advice and Information Service published information for those maintaining innocence and advised that “The Parole Board cannot refuse to release someone just because they are maintaining innocence, but it is harder. It is harder because it becomes more difficult to show evidence of a reduced risk of re-offending if the person has not done the treatment programmes.” This difficulty compounds the suffering for victims of miscarriages of justice.

This pressure is voiced to us by an overwhelming majority of our service users. The system craves a true admission of guilt, an acceptance of your criminal behaviour and visible, demonstrable remorse. Yet, a false admission of guilt and remorse by an innocent person at a parole hearing may hamper proving their innocence. In a case of mistaken identity, where a crime has taken place, it will tend to prevent later investigation into the perpetrator. Justice is not only denied to the prisoner but to the victims of crime and their families. Michael Naughton, founder of Innocence Network UK (INUK), who research and carry out work to raise public awareness of wrongful convictions, suggested the focus on new evidence by the Criminal Cases Review Commission, rather than an examination of serious problems with evidence at original trials, meant in many cases “that the dangerous criminals who committed these crimes remain at liberty with the potential to commit further serious crimes.” This is of equal relevance to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission north of the border.

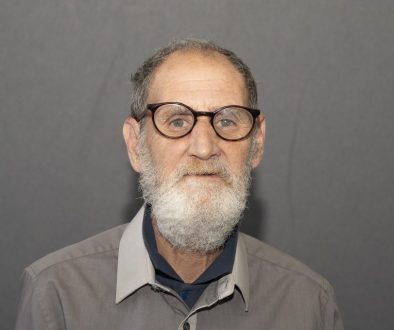

The reality is that in many jurisdictions, innocent prisoners are being denied parole, no doubt some of whom have died in prison. Our client, Robert Brown, maintained his innocence throughout his 25-year prison sentence, even going so far as denying himself parole by not admitting to a crime in which he played no part, ultimately serving more than a decade longer than his eligibility for parole. He was released on appeal in 2002. An evident paradox exists within our criminal justice system, between the reality of wrongful convictions and the premise that no person in prison should maintain innocence and deny their guilt.

Note: It is our organisation’s policy that applicants maintaining innocence and seeking casework support are not declined based on an admission of guilt in order to be paroled. The Parole Board for Scotland do not publish statistics on prisoners eligible for parole maintaining innocence.